The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1865 in the aftermath of the Civil War, abolished slavery in the United States. The 13th Amendment states: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Founding Fathers and Slavery

Despite the long history of slavery in the British colonies in North America, and the continued existence of slavery in America until 1865, the amendment was the first explicit mention of the institution of slavery in the U.S. Constitution.

While America’s founding fathers enshrined the importance of liberty and equality in the nation’s founding documents—including the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution—they conspicuously failed to mention slavery, which was legal in all 13 colonies in 1776.

Many of the founders themselves owned enslaved workers, and though they acknowledged that slavery was morally wrong, they effectively pushed the question of how to eradicate it to future generations of Americans.

Thomas Jefferson, who left a particularly complex legacy regarding slavery, signed a law banning the importation of enslaved people from Africa in 1807. Still, the institution became ever more entrenched in American society and economy—particularly in the South.null

By 1861, when the Civil War broke out, more than 4 million people (nearly all of them of African descent) were enslaved in 15 southern and border states.

Emancipation Proclamation

Though Abraham Lincoln abhorred slavery as a moral evil, he also wavered over the course of his career (and as president) on how to deal with the peculiar institution.

But by 1862, he had become convinced that emancipating enslaved people in the South would help the Union crush the Confederate rebellion and win the Civil War. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect in 1863, announced that all enslaved people held in the states “then in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

But the Emancipation Proclamation it itself did not end slavery in the United States, as it only applied to the 11 Confederate states then at war against the Union, and only to the portion of those states not already under Union control. To make emancipation permanent would take a constitutional amendment abolishing the institution of slavery itself.

READ MORE: Emancipation Proclamation

Battle Over the 13th Amendment

In April 1864, the U.S. Senate passed a proposed amendment banning slavery with the necessary two-thirds majority. But the amendment faltered in the House of Representatives, as more and more Democrats refused to support it (especially during an election year).null

As November approached, Lincoln’s reelection looked far from assured, but Union military victories greatly helped his cause, and he ended up defeating his Democratic opponent, General George McClellan, by a resounding margin.

When Congress reconvened in December 1864, the emboldened Republicans put a vote on the proposed amendment at the top of their agenda. More than any previous point in his presidency, Lincoln threw himself in the legislative process, inviting individual representatives to his office to discuss the amendment and putting pressure on border-state Unionists (who had previously opposed it) to change their position.

Lincoln also authorized his allies to entice House members with plum positions and other inducements, reportedly telling them: “I leave it to you to determine how it shall be done; but remember that I am President of the United States, clothed with immense power, and I expect you to procure those votes.”

Hampton Roads Conference

Last-minute drama ensued when rumors started flying that Confederate peace commissioners were en route to Washington (or already there), putting the future of the amendment in serious doubt.

But Lincoln assured Congressman James Ashley, who had introduced the bill into the House, that no peace commissioners were in the city, and the vote went ahead.

As it turned out, there were in fact Confederate representatives on their way to Union headquarters in Virginia. On February 3, at the Hampton Roads Conference, Lincoln met with them aboard a steamboat called the River Queen, but the meeting ended quickly, after he refused to grant any concessions.

13th Amendment Passes

On January 31, 1865, the House of Representatives passed the proposed amendment with a vote of 119-56, just over the required two-thirds majority. The following day, Lincoln approved a joint resolution of Congress submitting it to the state legislatures for ratification.

But he would not see final ratification: Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865, and the necessary number of states did not ratify the 13th Amendment until December 6.

While Section 1 of the 13th Amendment outlawed chattel slavery and involuntary servitude (except as punishment for a crime), Section 2 gave the U.S. Congress the power “to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

Black Codes

The year after the amendment’s passage, Congress used this power to pass the nation’s first civil rights bill, the Civil Rights Act of 1866. The law invalidated the so-called black codes, those laws put into place in the former Confederate states that governed the behavior of black people, effectively keeping them dependent on their former owners.

Congress also required the former Confederate states to ratify the 13th Amendment in order to regain representation in the federal government.

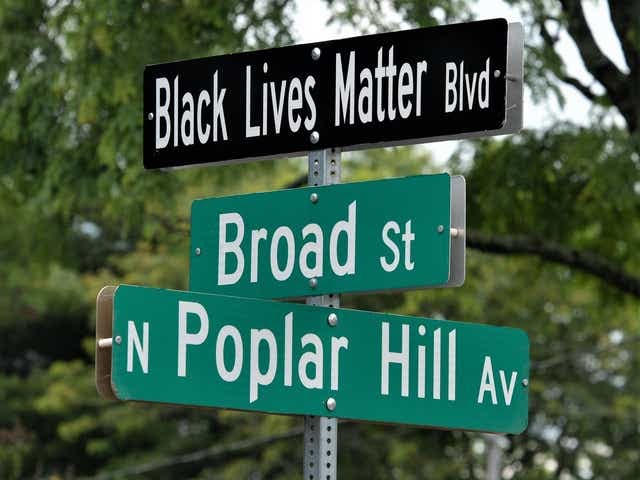

Together with the 14th and 15th Amendments, also ratified during the Reconstruction era, the 13th Amendment sought to establish equality for black Americans. Despite these efforts, the struggle to achieve full equality and guarantee the civil rights of all Americans has continued well into the 21st century.

Sources

13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Abolition of Slavery (1865), OurDocuments.gov.

The Thirteenth Amendment, Constitution Center.

Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W.W. Norton, 2010).

Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln

Citation Information

Author

Website Name

HISTORY

URL

https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/thirteenth-amendment

Access Date

Publisher

A&E Television Networks

Last Updated

June 19, 2020

Original Published Date

November 9, 2009